How To Fold Sheets

“Tuck the corners into the ears,” you tell me from across the vast ocean of a bed sheet. You shake it, snap it, and I rock backward from your energy. Half a beat behind, I fold my corners and think of a minuet I learned in second grade. The “ears” are pockets made by the fitted corners. On your side of this housekeeping dance, one ear folds into another, makes a seashell.

My sheet ears are sloppy, soft, as if I can’t hear how to make edges.

When I was little, you made my bed with hospital corners. Why we knew how hospitals folded their sheets so tightly is another story, a long one. Tuck the bottom end under the mattress in one swipe, then tuck each hanging-over side under the mattress in two more swipes. It should look like an envelope, you say.

This is a thing I learn. With you dead three years now, and hospital corners on my beds for nearly fifty years, I wake if a sheet comes untucked at my feet. It rarely does, because those corners are tight.

The day you refolded every sheet in my linen closet, you tucked ears into ears, made origami of pillow cases. When you were done, you labeled your work with index cards. “Yellow sheets, guest room,” you wrote. “Blue sheets, king sized.”

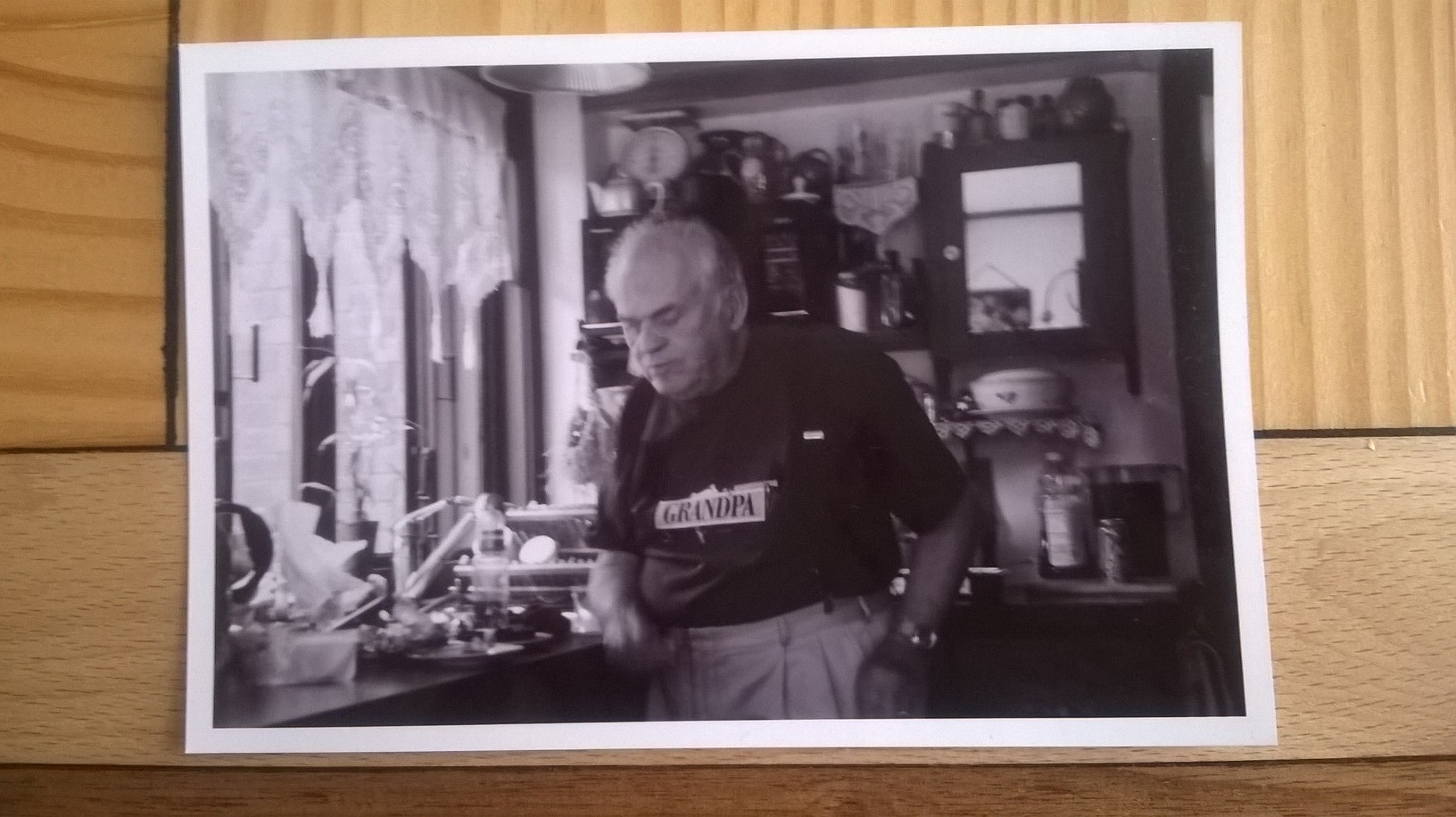

"My mother, holding me before I could fold anything."

- Jessica Handler is the author of Invisible Sisters: A Memoir, named by the Georgia Center for the Book one of the “Twenty Five Books All Georgians Should Read.” Atlanta Magazine called it the “Best Memoir of 2009.” Her second book, Braving the Fire: A Guide to Writing About Grief and Loss, was praised by Vanity Fair magazine as “a wise and encouraging guide.” Her nonfiction has appeared on NPR, in Tin House, Creative Nonfiction, Brevity, The Bitter Southerner, Drunken Boat, Newsweek, The Washington Post, More Magazine, and elsewhere. Honors include residencies at the Josef and Anni Albers Foundation, a 2010 Emerging Writer Fellowship from The Writers Center, the 2009 Peter Taylor Nonfiction Fellowship for the Kenyon Review Writers’ Workshop, and special mention for a 2008 Pushcart Prize. She teaches at Oglethorpe University and lectures internationally on writing well about trauma. www.jessicahandler.com.