How to Buy a Suit and Tie

Take your daughter with you. Shopping is better with company.

When the salesman asks what you are looking for, tell him you need a suit for your father, and everything he has is much too big now. Navy blue, not black. You want your father to look good, but nothing designer; you can almost hear him protesting such an extravagance.

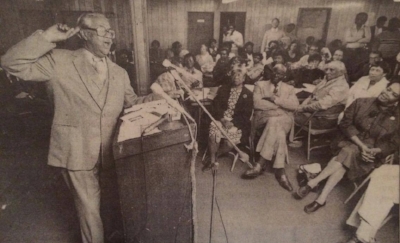

The author’s father, William Bryant, Jr (left) with his father, William Bryant, Sr in 2000.

Compare fabrics. Check the linings. Smooth the lapels. The salesman will narrow your choices to three suits. He will ask what the occasion is, hoping to be helpful.

Tell him it’s for a burial.

Don’t tell him that your father died a month after a 12-hour surgery for pancreatic cancer that he never woke from. That it was the same surgery you had just four months earlier. That you were cancer-free. That your surgery was performed by the doctor who pioneered it, but your father was too frail to travel that far. That your choices were to do nothing and watch the cancer kill him or attempt this surgery that might kill him. That you knew in any case that you would be in a department store buying your father’s last suit.

Breathe. Accept the salesman’s condolences. Choose a suit. Squeeze your daughter’s shoulder and have her select a tie. Play Earth, Wind, and Fire loudly on the car ride home.

In eighteen months, when your cancer returns and is in your lungs and liver and they tell you it is inoperable, select your own suit and tie.